Several years ago, I was given access to the digital files of Bassett Associates, a landscape architectural firm that operated for over 60 years in Lima, Ohio. This award-winning firm, which disbanded in 2017, was well known for its zoological design work and also did ground-breaking work in incorporating storm water retention as part of landscape site design. In addition to images of plans and site photographs, the files also included scans of sketches done by the firm's founder, James H. Bassett, which was artwork in its own right. I had been deliberating what the best way was to make these works publicly available and decided that this summer I would make it my project to set up an online digital archive featuring some of the images from the files.

Given my background as a Data Science and Data Curation Specialist at the Vanderbilt Libraries, it seemed like a good exercise to figure out how to set up Omeka Classic on Amazon Web Services (AWS), Vanderbilt's preferred cloud computing platform. Omeka is a free, open-source web platform that is popular in the library and digital humanities communities for creating online digital collections and exhibits, so it seemed like a good choice for me given that I would be funding this project on my own.

Preliminaries

The hard drive I have contains about 70 000 files collected over several decades. So the first task was to sort through the directories to figure out exactly what was there. For some of the later projects, there were some born-digital files, but the majority of the images were either digitizations of paper plans and sketches, or scans of 35mm slides. In some cases, the same original work was present several places on the drive with a variety of resolutions, so I needed to sort out where the highest quality files were located. Fortunately, some of the best works from signature projects had been digitized for an art exhibition, "James H. Bassett, Landscape Architect: A Retrospecive Exhibition 1952-2001" that took place in Artspace/Lima in 2001. Most of the digitized files were high-resolution TIFFs, which were ideal for preservation use. I focused on building the online image collection by featuring projects that were highlighted in that exhibition, since they covered the breadth of types of work done by the firm throughout its history.

The second major issue was to resolve the intellectual property status of the images. Some had previously been published in reports and brochures, and some had not. Some were from before the 1987 copyright law went into effect and some were after. Some could be attributed directly to James Bassett before the Bassett Associates corporation was formed and others could not be attributed to any particular individual. Fortunately, I was able to get permission from Mr. Bassett and the other two owners of the corporation when it disbanded to make the images freely available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. This basically eliminated complications around determining the copyright status of any particular work, and allows the images to be used by anyone as long as they provide the requested citation.

Image pre-processing

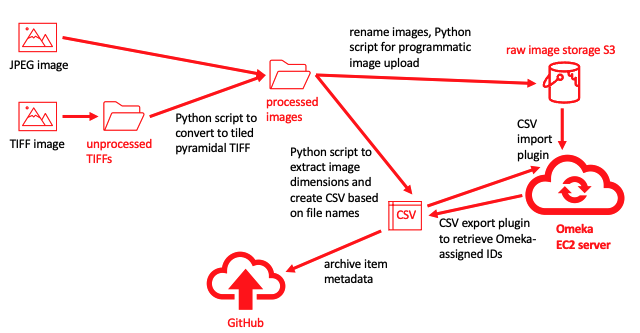

For several years I have been investigating how to make use of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) to provide a richer image viewing experience. Based on previous work and experimentation with our Libraries' Cantaloupe IIIF server, I knew that large TIFF images needed to be converted to tiled pyramidal (multi-resolution) form to be effectively served. I also discovered that TIFFs using CMYK color mode did not display properly when served by Cantaloupe. So the first image processing step was to open TIFF or Photoshop format images in Photoshop, flatten any layers, convert to RGB color mode if necessary, reduce the image size to less than 35 MB (more on size limits later), and save the image in TIFF format. JPEG files were not modified -- I just used the highest resolution copy that I could find.

Because I wanted to make it easy in the future to use the images with IIIF, I used a Python script that I wrote to converting single-resolution TIFFs en mass to tiled pyramidal TIFFs via ImageMagick. These processed TIFFs or high-resolution JPEGs were the original files that I eventually uploaded to Omeka.

Why use AWS?

One of my primary reasons for using AWS as the hosting platform was the availability of S3 bucket storage. AWS S3 storage is very inexpensive and by storing the images there rather than within the file storage attached to the cloud server, the image storage capacity could basically expand indefinitely without requiring any changes to the configuration of the cloud server hosting the site. Fortunately, there is an Omeka plug-in that makes it easy to configure storage in S3.

Another advantage (not realized in this project) is that because image storage is outside the server in a public S3 bucket, the same image files can be used as source files for a Cantaloupe installation. Thus a single copy of an image in S3 can serve the purpose of provisioning Omeka, being the source file for IIIF image variants served by Cantaloupe, and having a citable, stable URL that allows the original raw image to be downloaded by anyone.

I've also determined through experimentation that one can run a relatively low-traffic Omeka site on AWS using a single t2.micro tier Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) server. This minimally provisioned server currently costs only US$ 0.0116 per hour (about $8 per month) and is "free tier eligible", meaning that new users could run a Omeka on EC2 for free during the first year. Including the cost of the S3 storage, one could run an Omeka site on AWS with hundreds of images for under $10 per month.

The down side

The main problem with installing Omeka on AWS is that it is not a beginner-level project. I'm relatively well-acquainted with AWS and Unix command line, but it took me a couple months on and off to figure out how to get all of the necessary pieces to work together. Unfortunately, there wasn't a single web page that laid out all of the steps, so I had to read a number of blog posts and articles, then do a lot of experimenting to get the whole thing to work. I did take detailed notes, including all of the necessary commands and configuration details, so it should be possible for someone with moderate command-line skills and a willingness to learn the basics of AWS to replicate what I did.

Installation summary

In the remainder of this post, I'll walk through the general steps required to install Omeka Classic on AWS and describe important considerations and things I learned in the process. In general, there are three major components to the installation: setting up the S3 storage, installing Omeka on EC2, and getting a custom domain name to work with the site using secure HTTP. Each of these major steps includes several sub-tasks that will be described below.

The basic setup of an S3 bucket is very simple and involves only a few button clicks. However, the way Omeka operates, several additional steps are required for the bucket setup.

By design, AWS is secure and generally one wants to permit only the minimum required access to resources. But because Omeka exposes file URLs publicly so that people can download those files, the S3 bucket must be readable by anyone. Omeka also writes multiple image variant files to S3, and this requires generating access keys whose security must be carefully guarded.

You can manually upload files and enter their metadata by typing into boxes in the Omeka graphical interface. That's fine if you will only have a few items. However, if you will be uploading many items, uploading using the graphical interface is very tedious and requires many button clicks. To create an efficient upload workflow, I used the Omeka CSV import plugin. It requires loading the files via a URL during the import process, so I used a different public S3 bucket as the source of the raw images. I used

a Python script to partially automate the process of generating the metadata CSV and as part of that script, I uploaded the images automatically to the source raw image bucket using the AWS Python library (boto3). This required creating access credentials for the raw image bucket and to reduce security risks, I created a special AWS user that was only allowed to write to that one bucket.

Omeka installation on EC2

As with the set up of S3 buckets, launching an EC2 server instance just involves a few button clicks. What is trickier and somewhat tedious is performing the actual setup of Omeka within the server. Because the setup is happening at some mysterious location in the cloud, you can't point and click like you can on your local computer. To access the EC2 server, you have to essentially create a "tunnel" into it by connecting to it using SSH. Once you've done that, commands that you type into your terminal application are being applied to the remote server and not your local computer. Thus, everything you do must be done at the command line. This requires basic familiarity with Unix shell commands and since you also need to edit some configuration files, you need to know how to use a terminal-based editor like Nano.

The steps involve:

- installing a LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP) server bundle

- creating a MySQL database

- downloading and installing Omeka

- modifying Apache and Omeka configuration files

- downloading an enabling the Omeka S3 Storage Adapter and CSV Import plugins

Once you have completed these steps (which actually involve issuing something like 50 complicated Unix commands that fortunately can be copied and pasted from

my instructions), you will have a functional Omeka installation on AWS. However, accessing it would require users to use a confusing and insecure URL like

http://54.243.224.52/archive/

Mapping an Elastic IP address to a custom domain and enabling secure HTTP

To change this icky URL to a "normal" one that's easy to type into a browser and that is secure, several additional steps are required.

AWS provides a feature called an

Elastic IP address that allows you to keep using the same IP address even if you change the underlying resource it refers to. Normally, if you had to spin up a new EC2 instance (for example to restore from a backup), it would be assigned a new IP address, requiring you to change any setting that referred to the IP address of the previous EC2 you were using. An Elastic IP address can be reassigned to any EC2 instance, so disruption caused by replacing the old EC2 with a new one can be avoided by just shifting the Elastic IP to the new instance. Elastic IPs are free as long as they remain associated with a running resource.

It is relatively easy to assign a custom domain name to the Elastic IP if the AWS Route 53 domain registration is used. The cost of the custom domain varies depending on the specific domain name that you select. I was able to obtain `bassettassociates.org` for US$12 per year, adding $1 per month to the cost of running the website.

After the domain name has been associated with the Elastic IP address, the last step is to enable secure HTTP (HTTPS). When initially searching the web for instructions on how to do that, I found a number of complicated and potentially expensive suggestions including installing an Nginx front-end server and using an AWS load balancer. Those options are overkill for a low-traffic Omeka site. In contrast, it is relatively easy to get free security certificate from

Let's Encrypt and set it up to automatically renew monthly using Certbot for an Apache server.

Optional additional steps

If you plan to have multiple users editing the Omeka site, you won't be able to add users beyond the default Super User without additional steps. It appears that it's not possible to add more users without enabling Omeka to send emails. This requires setting up

AWS Simple Email Service (SES), then adding the SMPT credentials to the Omeka configuration file. SES is designed to enable sending mass emails, so being approved for production access requires applying for approval. I didn't have any problems getting approved when I explained that I was only going to use it to send a few confirmation emails, although the process took at least a day since apparently a human has to examine the application.

There are three additional plugins that I installed that you may consider using. The

Exhibit Builder and

Simple Pages plugins add the ability to create richer content. Installing them is trivial, so you will probably want to turn them on. I also installed the

CSV Export Format plugin because I wanted to use it to capture identifier information as part of my partially automated workflow (see following sections for more details).

If you are interested in using IIIF on your site, you may also want to install the IIIF Toolkit plugin, explained in more detail later.

Efficient workflow

Once Omeka is installed and configured, it is possible to just upload content manually using the Omeka graphical interface. That's fine if you will only have a few objects. However, if you will be uploading many objects, uploading using the graphical interface is very tedious and requires many button clicks.

The workflow described here is based on assembling the metadata in the most automated way possible, using file naming conventions, a Python script, and programatically created CSV files. Python scripts are also used to upload the files to S3, and from there they can be automatically imported into Omeka.

After the items are imported, the CSV export plugin can be used to extract the ID numbers assigned to the items by Omeka. A Python script then extracts the IDs from the resulting CSV and inserts them into the original CSVs used to assemble the metadata.

Notes about TIFF image files

If original image files are available as high-resolution TIFFs, that is probably the best format to archive from the preservation standpoint. However, most browsers will not display TIFFs natively, while JPEGs can be displayed onscreen. The practical implication of this is that image thumbnails are linked directly to the original highres image file. So when a user clicks on the thumbnail of a JPEG, the image is displayed in their browser, but when a TIFF thumbnail is clicked, the file downloads to the user's hard drive without being displayed. When an image is uploaded, Omeka makes several JPEG copies at lower resolution so that they can be displayed onscreen in the browser without downloading.

As explained in the preprocessing section above, the workflow includes an additional conversion step that only applies to TIFFs.

Note about file sizes

In the file configuration settings, I recommend seting a maximum file size of 100 MB. Virtually no JPEGs are ever that big, but some large TIFF files may exceed that size. As a practical matter, the upper limit on file size in this installation is actually about 50 MB. I have found from practical experience that importing original TIFF files between 50 and 100 MB can generate errors that will cause the Omeka server to hang. I have not been able to isolate the actual source of the problem, but it may be related to the process of generating the lower resolution JPEG copies. The problem may be isolated to using the CSV import plugin because some files that hung the server when using the CSV import were then able to be uploaded manually after creating the item record. In one instance, a JPEG that was only 11.4 MB repeatedly failed to upload using the CSV import. Apparently its large pixel dimensions (6144x4360) were the problem (it also was successfully uploaded manually).

The other thing to consider is that when TIFFs are converted to tiled pyramidal form, there is an increase in size of roughly 25% when the low-res layers are added to the original high-res layer. So a 40 MB raw TIFF may be at or over 50 MB after conversion. I have found that if I keep the original file size below 35 MB, the files usually load without problems. It is annoying to have to decrease the resolution of any souce files in order to add them to digital collection, but there is a workaround (described in the IIIF section below) for extremely large TIFF image files.

The CSV Import plugin

An efficient way to import multiple images is to use the

CSV Import plugin. The plugin requires two things: a CSV spreadsheet containing file and item metadata, and files that are accessible directly using a URL. Because files on your local hard drive are not accessible via a URL, there are a number of workarounds that can be used, such a uploading the images to a cloud service like Google Drive or Dropbox. Since we are using AWS S3 storage, it makes sense to make the image files accessible from there, since files in a public S3 bucket can be accessed by a URL. (Example of raw image available from an S3 bucket via the URL:

https://bassettassociates.s3.amazonaws.com/glf/haw/glf_haw_pl_00.tif)

One could create the metadata CSV entirely by hand by typing and copying and pasting in a spreadsheet editor. However, in my case, because of the general inconsistency in file names on the source hard drive, I was renaming all of the image files anyway. So I established a file identifier coding system that when used with file names would both group similar files together in the directory listing and also make it possible to automate populating some of the metadata fields in the CSV. The

Python script that I wrote generated a metadata CSV with many of the columns already populated, including the image dimensions, which it extracted from the EXIF data in the image files. After generating a first draft of the CSV, I then had to manually add the date, title, and description fields, plus any tags I wanted to add in addition to the ones that the script generated automatically from the file names. (

Example of completed CSV metadata file)

The CSV import plugin requires that all items imported as a batch be the same general type. Since my workflow was build to handle images, that wasn't be a problem -- all items were Still Images. As a practical matter, it was best to restrict all of the images in a batch to be for the same Omeka collection. If images intended for several collections were uploaded together in a batch, they would have had to be assigned to collections manually after upload.

Omeka identifiers

When Omeka ingests image files, it automatically assigns an opaque ID (e.g. 3244d9cdd5e9dce04e4e0522396ff779) to the image and generates JPEG versions of the original image at various sizes. These images are stored in the S3 bucket that you set up for Omeka storage. Since those images are publicly accessible by URL, you could provide access to them for other purposes. However, since the file names are based on the opaque identifiers and have no connection with the original file names, it would be difficult to know what the access URL would be. (Example:

https://bassett-omeka-storage.s3.amazonaws.com/fullsize/3244d9cdd5e9dce04e4e0522396ff779.jpg)

Fortunately, there is a CSV Export Format plugin that can be used to discover the Omeka-assigned IDs along with the original identifiers assigned by the provider as part of the CSV metadata that was uploaded during the import process. In my workflow, I have added additional steps to do the CSV export, then run

another Python script that pulls the Omeka identifiers from the CSV and archives them along with the original user-assigned identifier in an identifier CSV. At the end of processing each batch, I push the

identifier and metadata CSV files to GitHub to archive the data used in the upload.

In theory, the images in the raw image upload CSV file could be deleted. However, S3 storage costs are so low that you probably will just want to leave them there. Since they have meaningful file names and a subfolder organization of your choice, they would make a pretty nice cloud backup system that is independent of the Omeka instance. After your archive project is complete, you could change the raw image source bucket over to one of the

cheaper, low-access types (like Glacier) that have even lower storage costs than a standard S3 bucket. Because both buckets are public, you can use them as a means of giving access to the original high-res files by simply giving the Object URL to the person wanting a copy of the file.

Backing up the data

There are two mechanisms for backing up your data periodically.

The most straightforward is to create an

Amazon Machine Image (AMI) of the EC2 server. Not only will this save all of your data, but it will also archive the complete configuration of the server at the time the image is made. This is critical if you have any disasters while making major configuration changes and need to roll back the EC2 to an earlier (functional) state. It is quite easy to roll back to an AMI and re-assign the Elastic IP to the new EC2 instance. However, this rollback will have no impact on any files saved in S3 by Omeka after the time when the backup AMI was created. Those files won't hurt anything, but they will effectively be uselessly orphaned there.

The CSV files pushed to GitHub after each CSV import (

example) can also be used as a sort of backup. Any set of rows from the saved metadata CSV file can be used to re-upload those items onto any Omeka instance as long as the original files are still in the raw source image S3 bucket. Of course, if you make manual edits to the metadata, the metadata in the CSV file would become stale.

Using IIIF tools in Omeka

There are two Omeka plugins that add International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) capabilities.

The

UniversalViewer plugin allows Omeka to serve images like a IIIF image server and it generates IIIF manifests using the existing metadata. That makes it possible for the Universal Viewer player (included in the plugin) to display images in a rich manner that allows pan and zoom. This plugin was very appealing to me because if it functioned well, it would enable IIIF capabilities without needing to manage any other servers. I was able to install it and the embedded Universal Viewer did launch, but the images never loaded in the viewer. Despite spending a lot of time messing around with the settings, disabling S3 storage, and launching a larger EC2 image, I was never able to get it to work, even for a tiny JPEG file. I read a number of Omeka forum posts about troubleshooting, but eventually gave up.

If I had gotten it to work, there was one potential problem with the setup anyway. The t2.micro instance that I'm running has very low resource capacity (memory, number of CPUs, drive storage), which is OK as I've configured it because the server just has to run a relatively tiny MySQL database and serve static files from S3. But presumably this plugin would also have to generate the image variants that it's serving on the fly and that could max out the server quite easily. I'm disappointed that I couldn't get it to work, but I'm not confident that it's the right tool for a budget installation like this one.

I had more success with the

IIIF Toolkit plugin. It also provides an embedded Universal Viewer that can be inserted various places in Omeka. The major downside is that you must have access to a separate IIIF server to actually provide the images used in the viewer. I was able to test it out by loading images into the Vanderbilt Libraries' Cantaloupe IIIF server and it worked pretty well. However, setting up your own Cantaloupe server on AWS does not appear to be a trivial task and because of the resources required for the IIIF server to run effectively, it would probably cost a lot more per month to operate than the Omeka site itself. (Vanderbilt's server is running on a cluster with a load balancer, 2 vCPU, and 4 GB memory. All of these increases over a basic single t2.micro instance would involve a significantly increased cost.) So in the absence of an available external IIIF server, this plugin probably would not be useful for an independent user with a small budget.

One nice feature that I was not able to try was pointing the external server to the `original` folder of the S3 storage bucket. That would be a really nice feature since it would not require loading the images separately into dedicated storage for the IIIF server separate from what is already being provisioned for Omeka. Unfortunately, we have not yet got that working on the Libraries' Cantaloupe server as it seems to require some custom Ruby coding to implement.

Once the IIIF Toolkit is installed, there are two ways to include IIIF content into Omeka pages. If the Exhibit Builder plugin is enabled, the IIIF Toolkit adds a new kind of content block, "Manifest". Entering an IIIF manifest URL simply displays the contents of that manifest in an embedded Universal Viewer widget on the exhibit page without actually copying any images or metadata into the Omeka database.

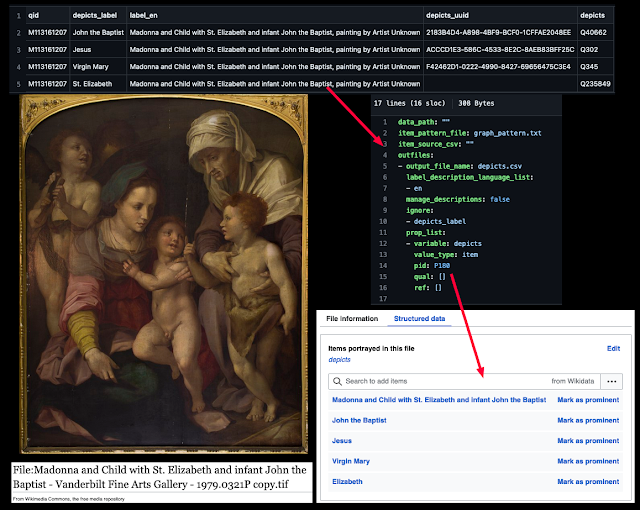

The second way to include IIIF content is to make use of an alternate method of importing content that becomes available after the IIIF Tollkit is installed. There are three import types possible to use to import items. I explored importing `Manifest` and `Canvas` types since I had those types of structured data available.

Manifest is the most straightforward because it only requires a manifest URL (commonly available from many sources). But the import was messy and always created a new collection for each item imported. In theory, this could be avoided by selecting an existing collection using the `Parent` dropdown, but that feature never worked for me.

I concluded that importing canvases was the only feasible method. Unfortunately, canvas JSON usually doesn't exist in isolation -- it usually is part of the JSON for an entire manifest. The `From Paste` option is useful if you are capable of the tedious task of searching through the JSON of a whole manifest and copying just the JSON for a single canvas from it. I found it much more useful to just create

Python script to generate minimal canvas JSON for an image and save it as a file, which could either be uploaded directly, or pushed to the web and read in through a URL. It gets the pixel dimensions from the image file, with labels and descriptions taken from a CSV file (the IIIF import does not use more information than that). These values are inserted into a JSON canvas template, then saved as a file. The script will loop through an entire directory of files, so it's relatively easy to make canvases for a number of images that were already uploaded using the CSV import function (just copy and paste labels and descriptions from the metadata CSV file). Once the canvases have been generated, either upload them or paste their URLs (if they were pushed to the web) on the IIIF Toolkit Import Items page.

The result of the import is an item similar to those created by direct upload or CSV import -- JPEG size variants are generated and stored and a small amount of metadata present in the canvas is assigned to the title and description metadata fields for the item. The main difference is that the import includes the canvas JSON as part of an Omeka-generated IIIF manifest that can be displayed in an embedded Universal Viewer either as part of an exhibit or on a Simple Pages web page. The viewer also shows up at the bottom of the item page.

Because there is no way to import IIIF items as a batch, nor to import metadata from the canvas beyond the title and description, each item needs to be imported one at a time and the metadata added manually, or added using the Bulk Metadata Editor plugin if possible. This makes uploading many items somewhat impractical. However, for very large images whose detail cannot be seen well in a single image on a screen, the ability to pan and zoom is pretty important. So for some items, like large maps, this tool can be very nice despite the extra work. For a good example, see the

panels page from the Omeka exhibit I made for the 2001 Artspace/Lima exhibition. It is best viewed by changing the embedded viewer to full screen.

|

Maximum zoom level using embedded IIIF Universal Viewer

|

One thing that should be noted is that like other images associated with Omeka items, image import using the IIIF Toolkit generates size versions of the image. A IIIF import also generates an "original" JPEG version that is much smaller than the pyramidal tiled TIFF uploaded to the IIIF server. This means that it is possible to create items for TIFF images that are larger than the 50 MB recommended above. An example is the

Binder Park Master Plan. If you scroll to the bottom of its page and zoom in (above), you will see that an incredible amount of detail is visible because the original TIFF file being used by the IIIF server is huge (347 MB). So using IIIF import is a way to display and make available very large image files that exceed the practical limit of 50 MB discussed above.

Conclusions

Although it took me a long time to figure out how to get all of the pieces to work together, I'm quite satisfied with the Omeka setup I now have running on AWS. I've been uploading works and as of this writing (2023-08-06), I've uploaded

400 items into

36 collections. I also created an

Omeka Exhibit for the 2001 exhibition that includes the panels created for the exhibition using

an "IIIF Items" block (allows arrowing through all of the panels with pan and zoom),

a "works" block (displaying thumbnails for artworks displayed in the exhibition), and

a "carousel" block (cycling through photographs of the exhibition). I still need to do more work on the landing page and on styling of the theme. But for now I have an adequate mechanism for exposing some of the images in the collection on a robust hosting system for a total cost of around $10 per month.